4,000 BC to 2,350 BC

Lyn Palmer

Introduction

The Neolithic, the ‘new Stone Age’, began in Britain around 6000 years ago. It is often regarded as a major turning point in mankind’s history: a time of widespread change and innovation in technology and society. We find the first certain evidence of arable farming and pastoralism. Pottery was produced in Britain for the first time and new forms of flint tools made. Major monuments were constructed and some members of society were buried within chambered tombs or earthen long barrows. Recent interpretations suggest some of these changes took place over many centuries. The shift from a mobile hunting and gathering lifestyle to more permanent settlement may have been very gradual.

It is likely that during the early Neolithic much of the Kent landscape was still covered with deciduous woodland. Clearance of woodland, to provide pasture and crop fields, was patchy and at first may not have been permanent leading to woodland regeneration in some areas. The first domesticated animals were sheep, pigs and goats. Barley and wheat were planted. The population grew, but, although people became food-producers, wild foods were still an important part of their diet.

Burial monuments

Surviving evidence for the Neolithic is dominated by ceremonial monuments, built by moving and shaping enormous quantities of earth, stone and wood. Archaeologists differentiate these monuments by their form, and we know them as long barrows, henges, causewayed enclosures, cursus and stone or wooden circles. Many were highly visible in the landscape, perhaps marking boundaries or territory newly claimed by these first farmers. Concepts of property, ownership and inheritance must have evolved as land became increasingly divided up between different groups.

The most dramatic evidence of the earlier Neolithic in Kent is two groups of long barrows, one centred on the Medway Valley, the Medway Megaliths, the other on the Stour Valley. Construction techniques differ; the Medway barrows are ‘megalithic’, with a chamber made of large stones, and the Stour barrows made wholly of earth. It is likely that some of Kent’s barrows were among the earliest examples of this type of monument in Britain.

Long barrows in the Medway group show similarities to those in the central south of England, such as West Kennet, and the earthen Stour long barrows are similar to those in areas lacking usable stone, such as Haddenham in Cambridgeshire.

The Medway Megaliths were built to the east and west of the river Medway. The western group are Coldrum, Addington, and Chestnuts. Coldrum is the best preserved, with some of its original covering mound and curb stones still intact. The huge stone slabs of the burial chamber stand uncovered. The site is a short walk from a car park provided for visitors. At The Chestnuts (on private land), the stone slabs have been re-erected to form the chamber.

Image: Kit's Coty, Aylesford

The eastern group has four definite monuments and several other possible examples. Kits Coty’s chamber retains the capstone atop three upright stones, Lower Kit's Coty (also known as the Countless Stones), is a tumble of large stones which once formed a chamber, whilst White Horse Stone is visible as just one huge slab of upright stone. Warren Farm has now virtually disappeared, but was once a stone chamber.

Image: Little Kit's Coty, Aylesford

There are three barrows in the Stour Valley group; Juliberrie’s Grave and two others at Boughton Aluph and Elmstead. Juliberrie’s survives as a long mound; excavation here uncovered animal bone and flint tools, but no burial, perhaps due to some of its length being quarried away.

Settlement evidence

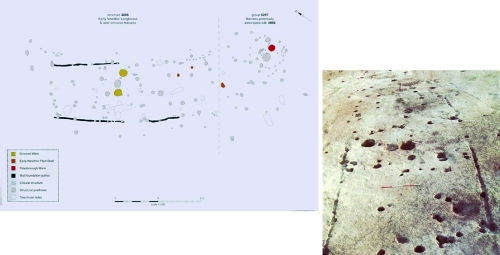

There is still little evidence for permanent settlement in the shape of large buildings, with only around 40 such known sites in Britain. Kent is fortunate though, for recent excavations at White Horse Stone, near Maidstone, uncovered a substantial timber structure. It was built around 5500 years ago and may have been used for communal or ceremonial purposes rather than as a domestic dwelling, especially given its proximity to the eastern Medway Megaliths group.

Image: Neolithic longhouse at White Horse Stone

The most common evidence for settlement in this period is pits, usually shallow and fairly small. Artefacts were deliberately chosen and placed in many, as at Wingham. Worked flints from this pit could all be fitted back together into one nodule. A bone comb, pottery and part of a saddle quern (for grain-grinding) accompanied the flints.

Enclosures

The discovery of Kent’s causewayed enclosures and possible cursus is recent, coming about through road and housing development.

There are at least four known causewayed enclosures, two at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, and two near Ramsgate, at Chalk Hill and Pegwell Bay. There may be another at Burham and a further one near Eastry. Chalk Hill had three ditches forming an enclosure about 150m in diameter. Each ditch contained a different type of deliberately-placed deposit; the inner had cremated bone, the middle, worked flint tools, and the outer, pottery, shells and bone. Two skulls were also found.

Two parallel ditches, 35m apart, overlying the Chalk Hill enclosure, have been interpreted as a small section of cursus. This is the first example of this type of monument discovered in Kent. Its length is unknown, but its eastern route would lead into a valley down to Pegwell Bay, its western route towards a complex of barrows at Lord of the Manor.

Tool manufacturing

Stone tools made by Neolithic people are found in large numbers in Kent, particularly on the high chalkland in the east. Over 80% of the Neolithic axes found in south-eastern England are made of flint, widely available in the area, although no mine, such as those in Sussex and Norfolk, has yet been discovered in Kent. Axes from further afield, such as the Lake District, Wales and Cornwall, have also been found in the county, revealing the long distances that goods travelled.

The end of the neolithic

During the later Neolithic, new types of monument were built in Britain, such as henges, and stone or wooden circles. Kent has one example of a henge at Ringlemere near Sandwich, though others have been suggested. The site was excavated after the discovery of a gold cup here by a metal detectorist. The henge had a 42 m diameter ditch and was overlain by a later Bronze Age mound. Huge amounts of grooved ware, Neolithic pottery associated with ceremonial sites, were found. The henge appears to date from the earlier part of the third millennium BC.

The majority of stone circles in Britain exist in the west and north of the country. None has yet been discovered in Kent; whether this is due to intensive farming practice and dense settlement in the county having destroyed them, or whether the tradition of circle-building was missing here, is unknown.

The Neolithic ended around 2500BC, when knowledge of metal working began to spread and stone was no longer the only available material for tools. The Bronze Age had arrived.