AD 43 to AD 410

Lyn Palmer

Introduction

Britain finally became part of the Roman empire after the invasion of AD43, following unsuccessful attempts or expeditions in 55 and 54BC. The country became Rome’s north-westerly outpost, its acquisition driven by the political ambitions of the Emperor Claudius.

The evidence for Roman Kent is very good, both in its remains and in written texts. Contact with Rome brought a level of literacy, glimpses of which can be seen during the previous century on the coins of local British rulers. Archaeologists now have written sources to work with for the first time, albeit written by the victors.

Early Roman Kent

The tribal area of Roman Kent was known as the civitas Cantiacorum. Julius Caesar had talked of four regions with four kings; the exact boundary of the civitas is unknown and, although it is unlikely to have been exactly the same as the Iron Age boundaries, the new Roman administration may have more or less crystallised an earlier political geography. Administration of the new territory was left mainly to trusted local aristocrats whose people were treated as one entity – the Cantiaci.

Roads and Towns

It is likely that the Roman army landed at Richborough (Rutupiae). A military base was quickly established here after the invasion and storage facilities built to supply the garrison. Around AD80-90 a colossal 25-metre high marble-clad arch was erected overlooking the harbour – a statement of conquest and an imposing sight for new arrivals. The road now known as Watling Street began its journey under the arch, passing through Canterbury (Durovernum) and Rochester (Durobrivae) on its way to London (Londinium). During the second and third centuries a town which lasted into the later Roman period grew up outside the fort. In the later third century a new fort was built, by which time the ruinous arch had been converted into a watch-tower.

Image: Richborough Roman Fort

Watling Street, was in place soon after the conquest, perhaps making use of earlier trackways, and became a focus for settlement. Coastal transport was also important, and many of the settlements that became important in the Roman period were located on river estuaries. Other areas with concentrations of sites are Thanet, the east Kent chalk and along the rivers Medway, Stour, Darent and Cray. Canterbury became the civitas centre and a road system radiated from here to Reculver (Regulbium), Dover (Portus Dubris) and Lympne (Portus Lemanis).

Roman Canterbury lies buried beneath the modern city, but many archaeological excavations have taken place, most recently in the Whitefriars project. A late Iron Age settlement already existed; redevelopment on Roman lines took place around AD70-80, a theatre was built by AD90 and a road grid established in the early second century.

Monumental public buildings were also erected then, including a major temple whose size and ornamentation were comparable with that at Bath. The town was enclosed within defensive walls in the later third century but declined throughout the fourth century.

Rural settlement

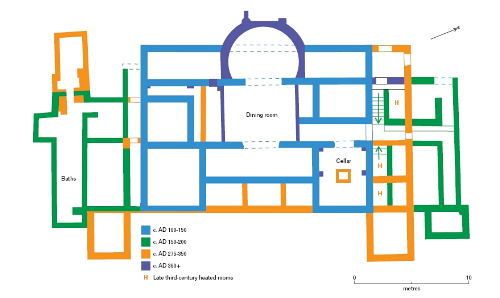

Roadside settlements grew, as at Monkton, Thanet, and Westhawk Farm, Ashford. Much of the countryside’s population continued to live in timber houses, round or rectangular. The pro-Roman elite, however, aspired to Roman culture. They began building rural villas in stone or half timber, sometimes on the same spot as previous homes, as at Thurnham and Eccles. The first stages of Eccles, overlooking the Medway Valley, were built perhaps only a decade after the invasion. Surprisingly though, given Kent’s role as Rome’s gateway to Britain, few villas were built before the end of the first century and most of these were in west Kent. The Medway and Darent river valleys both have a concentration; there is also a group south of the Swale east of Rochester. Nearly 100 villas are known in Kent; notable examples include Lullingstone, Darenth, Wingham and Folkestone. Lullingstone began around AD100 as a modest building and was added to and altered over more than two centuries before its final destruction by fire in the early 5th century. It is remarkable for its mosaics and early Christian iconography. No villas are known in the Weald, perhaps because the clay was difficult to farm, but their absence may simply reflect less archaeological investigation in that area.

Image: Plan of Lullingstone Roman villa

Religion

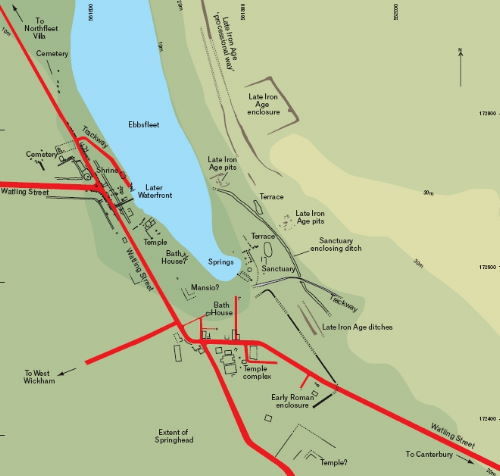

Pagan religion flourished at Springhead (Vagniacis). Sited on Watling Street at natural springs, travellers passed through, and a major religious centre grew out of an earlier Iron Age ritual site. At least seven temples were built near the springs and many votive offerings have been found. A settlement grew up, catering to visitors needs, with shops and workshops. The dead were catered for too; over 500 burials were found in the recently excavated cemetery at Pepperhill, to the south of the town. Kent has plentiful burial evidence compared with the rest of Britain, including walled cemeteries such as that at Springhead, and barrows, notably at Holborough and Snodland. The county’s funerary evidence is similar to that on the continent.

Image: Plan of Springhead Roman religious centre

Industry

Iron production was an important industry in the Weald, where the raw materials of ore and timber were found. Industrial scale production of pottery took place too, the main centres being at Canterbury and on either side of the Thames/Medway estuary. Pottery was also imported; the Pudding Pan wreck sank in Herne Bay with a cargo of samian ware and the pots are brought up in fishing nets today. Kentish ragstone, quarried from around Maidstone, was used for building, including Londinium’s walls. A barge carrying this cargo sank in the Thames near Blackfriars.

The Roman fleet

Kent, unlike the rest of southern Britain, retained a military presence after the initial invasion. This was probably connected with the importance of the harbour facilities in maintaining miltary and other supplies. Kent has one of the largest concentrations of fortifications in the country aside from Hadrian’s Wall. Tiles stamped with the initials of the Classis Britannica, the British fleet, have been found at the forts at Richborough, Dover and Lympne, and in some quantity at Wealden iron-smelting sites, indicative of links with the military. From Ickham, close to Richborough, comes evidence for military supply through the state in the form of fourth century lead seals discarded from opened sacks. 3 water mills and associated settlements stood here, with evidence for lead, copper, iron and pewter working.

Dover was developed as a major port, with a 2-acre fort from the early second century as a base for the Classis Britannica. A pair of lighthouses (pharos) originally some 24 metres tall, stood on the headlands either side of the harbour. One still remains to a height of 19 metres. The ‘Roman Painted House’ , outside the fort, is thought to have been a mansio, or guest house, for senior official visitors. Other evidence for the navy comes from Lympne, where an inscribed altar to Neptune was erected by a prefect of the fleet in c. AD135/45.

Image: Dover Roman 'Pharos'

The end of Roman Kent

The 'Saxon Shore forts’ describes the late Roman defences built around the south east of Britain when the area was under threat by continental ‘barbarians’. In Kent these include Lympne, Dover, Richborough and Reculver. They were probably not a systematically planned defence system; all have high walls but little evidence of large garrisons except at Reculver.

Troops were withdrawn from the end of the fourth century onwards to deal with incursions elsewhere in the Roman empire, the last of them leaving from Richborough. The end of Roman Britain is conventionally set at AD406.