AD 410 to AD 1066

Lyn Palmer and Andrew Richardson

Introduction

After the end of Roman occupation in the early fifth century, peoples from the continent, mainly northern Germany and southern Scandinavia, began to settle in eastern areas of Britain. From the middle of the 5th century onwards, they began to gain dominance over the native population. The infrastructure of Roman Kent gradually fell apart and rural villas and towns were abandoned, their buildings eventually falling into decay. Coinage and wheel-thrown pottery also disappeared.

Once these incomers, whom we call ‘Anglo-Saxons’ since they included people from the Angle and Saxon tribes, had settled, they began to intermingle with the people of Britain. The origin myths for Kent, which were probably written down for the first time in the early 7th century, relate that the settlers in Kent were Jutes from southern Scandinavia, a picture that has some support from archaeological evidence. These myths also name the warrior leaders Hengest and Horsa as defeating the British in Kent, although it is not known whether these were real figures or not.

The Kingdom of Kent

Kent has produced a wealth of archaeological evidence from the Anglo-Saxon period and has the earliest written sources in England. By the early 7th century the texts give details of a series of kings and their laws. They became politically powerful, influencing other southern and eastern kingdoms. East and west Kent were perhaps originally separate kingdoms; during the 7th and 8th centuries pairs of kings ruled, the more senior in the east. ‘Kent’ was created in this period; the original powerbase of the kingdom seems to have lain east of the River Stour. By the end of the 6th century, however, it included at least the area of the modern county, consisting perhaps of around 20-30 large estates, each with a centre. Many estates were controlled by the King, such as Eastry in the east, Milton Regis in the centre and Dartford in the west. After AD 825, Kent became part of the large West Saxon kingdom; for a while the heir to the throne on Wessex bore the title ‘King of Kent’, but by the end of the 9th century the title was abandoned.

Burial evidence

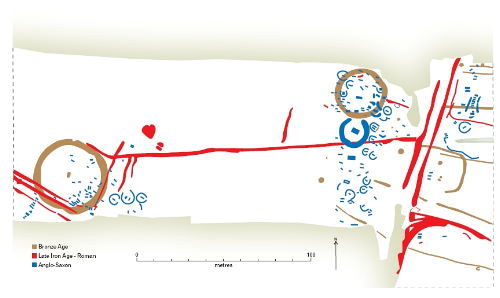

Most Anglo-Saxon archaeological evidence comes from burials; there is comparatively little settlement evidence. Early burial sites often incorporated the still-visible mounds of Bronze Age barrows, as at Cliffs End, Ringlemere and Saltwood. The majority of cemeteries are known from the area between the former Thames marshlands and the lower reaches of the North Downs, and include the Isle of Thanet and the chalk south of the Wantsum Channel. East Kent has some of the largest Anglo-Saxon cemeteries in Britain, with several hundred burials each at Saltwood, Buckland, Ozengell and Sarre. Some cemeteries, such as Buckland, were in use for centuries; the communities they served were evidently long-lived.

Image: Saltwood Anglo-Saxon cemetery showing prehistoric ring-ditches

The earlier Anglo-Saxons buried their dead fully clothed, and placed objects in the grave. Dress ornaments, weapons, pottery and glass have survived in quantity. The evolving styles of brooches and their placement on women’s costume have enabled archaeologists to trace immigration patterns and influences from the continent from the fifth to the seventh century. Similarly, weapons in male burials evolved over time, although by the later seventh century weapon burial had largely ceased.

5th and 6th century grave goods in west Kent are similar to those in other areas such as Surrey, which display a northern German (Saxon) culture. Cemeteries in the west include Northfleet and Orpington (in Greater London). Women in these areas often wore saucer and disc brooches in pairs with beads of amber or glass between them. Grave goods in east Kent have a distinctive ‘Kentish’ style, representing a fusion of southern Scandinavian (Jutish) and Frankish craft-working and art stryles. East Kentish styles spread to west Kent by the later 6th century, as this area came under east Kentish control.

Kent has no equivalent to the royal burials of Sutton Hoo or Prittlewell, but many spectacular and beautiful objects have been found here, including rock crystal balls encased in silver, perforated silver spoons and fluted glass goblets. The Kingston Brooch embodies the superb workmanship and materials used in many pieces of jewellery made in Kent. It was found in the burial of a very high status woman who probably had Kentish royal connections.

By the end of the 7th century fewer grave goods were included in burials. Fashions had changed too, becoming influenced in particular by Italy as Kent’s conversion to Christianity took hold following St Augustine’s mission of AD 597. Bishoprics were established in Canterbury and Rochester and monasteries built across Kent. Pagan worship was banned in the mid 7th century.

The Anglo-Saxon church

The earliest Anglo-Saxon churches in Britain are in Kent, dating from around AD600. The Archbishopric at Canterbury was founded c.AD 598 and the bishopric at Rochester in AD 604, the first structures now survive only as buried foundations. By the Norman conquest, around 400 mainly timber churches had been built, often replaced by later stone medieval churches. Fragments of Anglo-Saxon stone churches have survived at Lyminge, St Mary-in-Castro at Dover, Northfleet and at Minster-in Sheppey, c.670. St Martin’s parish church, Canterbury, survives as a roofed building and is probably the chapel used by Queen Bertha, whose pagan husband Ethelbert was converted by St Augustine.

Settlement evidence

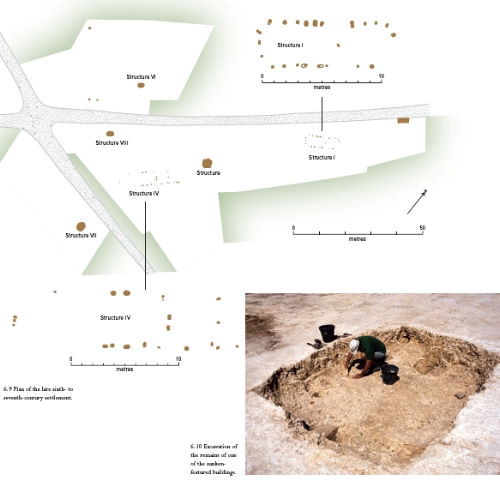

Settlements found in Kent have generally been small and rural, apart from those at Canterbury and Dover. Within the Roman walls of these two towns the Anglo-Saxons built wooden structures. Houses with floors below ground level (sunken-featured buildings, known as SFB’s) were built in Canterbury from around the mid-5th century and in Dover from the 7th century. Large timber halls uncovered in both these towns may have been royal residences.

There is evidence that Anglo-Saxons also reused Roman buildings, such as at Deerton Street near Faversham. Settlements were sometimes built around former Roman villas, as at Northfleet during the 6th and 7th centuries. The Northfleet site is in a river valley, but some settlements have been found on upland, as at Church Whitfield, near Dover. A concentration of early settlements have been found on Thanet, including the settlement associated with the Sarre cemetery, at Manston Road, Ramsgate, and at Monkton.

Image: Church Whitfield Anglo-Saxon settlement

Maritime evidence

A 7th to 9th century fishing, market and saltmaking site has been excavated at Sandtun near Lympne. Evidence for maritime activity elsewhere is sparse, but Kent does possess the earliest clinker-built boat known in Britain. The Graveney boat was uncovered in the marshes by the Swale in 1970 and has been dated to the 10th century. The power of water was harnessed at Ebbsfleet, where a rare tidal watermill was discovered. Dating to c.AD 700, it is one of the earliest examples of its kind in the country.

Image: Ebbsfleet Anglo-Saxon watermill under excavation

Viking raids

Historical texts talk of Kent suffering from Viking raids, although little archaeological evidence has yet been found. The first big raid was on Sheppey in AD 835 and attacks continued, targeting Rochester, Canterbury and the monasteries. In the AD 850s the Vikings supposedly overwintered on Sheppey and Thanet. A force besieged Rochester in AD 885, but was eventually driven away by Alfred the Great. He also oversaw their removal in 892, when the Vikings set up camp at Appledore and Milton Regis after landing in Romney Marsh. The most vicious period of attacks was from 980 onwards, when Thanet was devastated. Canterbury was sacked in 1011 and Archbishop Alphege murdered. The leader of these attacks, Cnut, was finally defeated in 1017 and his army departed.

Anglo-Saxon coinage

Material culture is much less distinctively Kentish from the 7th century onwards and becomes part of a wider English identity. However, Kent’s geographical position, combined with its historic position as the foundation of the English church, ensured that it remained wealthy and a focus for trade and culture throughout the later Anglo-Saxon period, despite the Viking attacks. Kent was the first area to mint coins in the post-Roman period – gold ‘Thrymsa’s’ in the 7th century. Silver pennies, known to us as ‘Sceats’ were minted here during the later 7th and 8th centuries and suggest that Kent was part of a thriving trade network in the southern North Sea at this time.

The Anglo-Saxon period draws to a close with the Norman invasion of 1066.