2,350 BC to 700 BC

Lyn Palmer

Introduction

The Bronze Age started in Britain about 4,300 years ago and ends around 2,700 years ago (2,500 – 700 BC). It is so-named because the use of metal, in particular the combination of copper with tin to produce bronze, became widespread. The new alloy was a harder, more useful metal for tools and weapons. The first part of the period can be described as the Copper Age, or 'Chalcolithic' with full emphasis on copper-alloy (bronze) production by about 2,150 BC.

Flint tools, which had been used for thousands of years, were gradually superseded but still widely used in the earlier Bronze Age. Of those found today, many come from the present ground surface, giving us little information about associated settlements, but some accompany burials and others are found during excavation of domestic sites.

Farming

Farming, introduced into Britain in the Neolithic, became more organised as the Bronze Age progressed, although it seems that livestock rearing was more prevalent than arable production. At Holywell Coombe, near Folkestone, archaeologists uncovered marks that had been gouged into the earth by a prehistoric plough, known as an ard. Many layers had built up above them as people farmed the landscape through the centuries. These layers contained pig and cow bones and post holes where animal enclosures and perhaps buildings had stood. The landscape was increasingly divided up with walls, fences, banks and ditches, formalising its ownership, as Coldharbour Road, Gravesend.

Burial and ritual

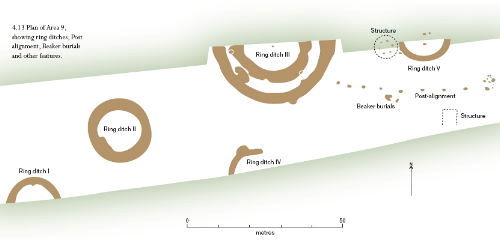

The commonest type of earlier Bronze Age remains are barrows, round or more rarely oval mounds often covering a central burial, with an encircling ditch. Further burials could be inserted into the mound or its surrounds as time passed. Very few barrows are still visible to the naked eye, as many have been flattened by ploughing or development. Kent’s barrows have suffered more than those in some other counties where land was more commonly left as pasture for grazing.

Aerial photographs have led to the discovery of many more barrows over the last few decades. Soil in their ditches holds greater moisture and shows up as a darker ring of more fertile vegetation. Thanet (then still separated from north east Kent by a sea channel) and east Kent have the majority of known barrows on their chalkland, but it may be that the evidence for them elsewhere has been destroyed. Barrows are often grouped together, as at Monkton in Thanet. At Ringlemere, barrows were built within and adjacent to the earlier henge monument, making use of what was already a special place. Barrow-building gradually declined throughout the Bronze Age.

Image: The barrow cemetery at Monkton

A package of grave goods existed associated with beakers, early Bronze Age pots named after their shape. Burials could contain one, or several, beakers, and other objects which had sometimes travelled a long way from their original source. At Manston, in addition to a flint knife and a beaker, the grave contained a perforated jet button. A Monkton burial also contained jet beads, a material that originates from Yorkshire. Exchange, gift or trade had brought the jet to Kent. Other beaker grave goods include archer’s wristguards, as at St. Peter’s.

Trade

Prestige appears linked to the acquisition of goods. A social elite emerged in the later Bronze Age based on the ability to compete for possessions. Kent’s location gave it obvious trade advantages. Evidence of cross-Channel trade can be seen in the Langdon Bay hoard, a cargo of scrap bronze tools and weapons lost overboard near Dover. They were originally made in France, but were destined for smelting down in England. The spectacular Dover Boat, built around 3500 years ago and perhaps 12m long, was discovered in water-laden ground during construction of a new underpass in Dover. It was a seaworthy craft, and may have plied along the Channel. It can be seen today in an award-winning Bronze Age gallery in Dover Museum.

Image: The Dover Boat

Increasingly specialised craft skills and farming techniques produced a surplus of marketable products. The perishable materials of many crafts, however, have been lost to us forever. We find loom weights used in weaving, but the textiles have vanished. Salt production along the Thames estuary has left us ‘briquetage’, the pottery used to harvest it, but the product itself is archaeologically invisible.

Metalworking

In contrast, the products of metalworking have survived. The amount of recovered weapons and tools makes it possible to trace evolutions of style and design throughout the period. It is difficult though, to explain the deliberate burying of bronze metalwork in hoards, effectively taking it out of circulation. Various reasons have been put forward for hoard burial; as ritual offerings, to increase the scarcity of remaining metalwork or to hide precious goods from marauders. Many of these hoards have been found in Kent, two examples are Hollingbourne and Minnis Bay, Birchington. Often the metal is fragmentary, as if deliberately broken up to be recycled; these are known as ‘founders hoards’ such as the one found at Allhallows. Moulds for bronze casting have also been found, as at Highstead.

Gold is found occasionally, either in burials or deliberately buried in groups of objects. One extraordinary find was the Ringlemere Cup, discovered by a metal detectorist in east Kent in 2001. The cup is about 11cm high, with a handle on one side. It is one of a very small number of metal cups from early Bronze Age Europe and is remarkably similar to a gold cup from Rillaton in Cornwall, which was found in 1837. Both are now in the British Museum.The practice of depositing precious items in water probably began in the Bronze Age. There have been several gold finds in the Medway Valley, for example, torcs (neckrings) and bracelets at Aylesford. Surprisingly though, there is no Bronze Age gold from north east Kent, where there is a concentration of bronze hoards.

Image: Middle bronze age torcs from the River Medway at Aylesford

The later bronze age

Around 3500 years ago the remains of settlements begin to dominate our evidence for Kent’s later Bronze Age. Monument building for the dead declines; for a few centuries in the later second millennium BC cremations in large pots were sometimes inserted into already-existing barrows or laid in cemeteries with very small, or no, mounds, as at Bridge, near Canterbury. After 3000 years ago there is no longer a regular recognisable burial rite in Kent for some centuries.

The coast and river valleys were favoured settlement areas. The Medway and Stour valleys both have concentrations of occupation sites; rivers would have been important in the trade and communication network. Houses were usually round, and often within an oval or rectangular enclosure. Examples have been found at Ramsgate and Highstead. Kingsborough Farm, Sheppey, had several enclosures, for both domestic and burial purposes. People were creating permanent holdings, tied to the land that they farmed and grazed their animals on. They were also making their status evident in an age of conspicuous consumption.

Around 3000 years ago, knowledge of iron working began to spread from the continent into this country. The Weald of Kent’s iron sources made it an important centre; by 700BC the Iron Age had begun.